Budget

Budget

Budget.

A budget is a written record of income and expenses during a specific time frame, typically a year.

You use a budget as a spending plan to allocate your income to cover your expenses and to track how closely your actual expenditures line up with what you had planned to spend.

An essential part of personal budgeting is creating an emergency fund, which you can use to cover unexpected expenses. You also want to budget a percentage of your income for saving and investing, just as you budget for food, housing, and clothing.

Businesses and governments also create budgets to govern their expenditures for a fiscal year -- though like individuals they make regular adjustments to reflect financial reality. And, like individuals, businesses and governments can find themselves in trouble if their spending outpaces their income.

budget

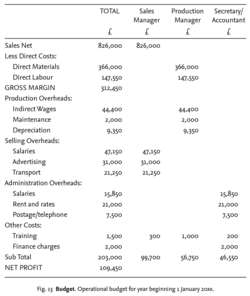

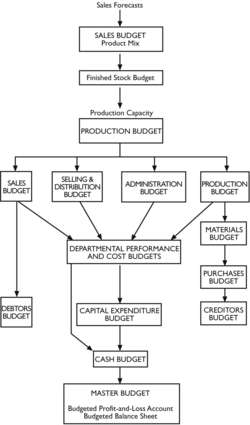

- a firm's predetermined plan (expressed in quantitative or financial terms) for a given future period. The sales budget is generally compiled with the aid of sales forecasts and shows quantities and values of planned sales broken down by product group, area and type of customer. The linked selling costs budget shows planned salesforce and advertising costs; while the distribution costs budget shows planned distribution activity measured in packages handled, tonnage, etc. and associated warehousing and transport costs. Once the sales budget is complete then the consequences of planned sales can be spelled out in the production budget, after making allowance for any planned changes in finished goods stock. The production budget specifies the quantities of various goods to be produced and the planned DIRECT MATERIALS, DIRECT LABOUR and factory OVERHEADS associated with these production plans, with a purchases budget showing planned purchases of raw materials. The administration costs budget shows the planned cost of personnel, accounts and similar administrative departments.

The capital expenditure budget is concerned with planned expenditure on FIXED ASSETS, itemizing what new or replacement assets are to be acquired during the forthcoming period and making the necessary finance available. The cash budget shows the overall cash position, with cash inflows resulting from planned sales and cash outflows resulting from planned expenditure on raw materials, wages, capital expenditure, etc. (so that any anticipated cash surpluses or deficits show up in good time to deal with them). Finally the master budget aggregates all the former budgets to produce a budgeted PROFIT-AND-LOSS ACCOUNT and a budgeted BALANCE SHEET, showing what profit will be earned and what the year-end position will be, provided that actual operations go according to plan. Fig. 12 shows the steps involved in developing a budget while Fig. 13 overleaf shows a simple company budget. See BUDGETING, BUDGETARY CONTROL.

- a statement of the government's financial position which is used for the government's economic and social welfare programmes and as part of FISCAL POLICY in managing the level and distribution of spending in the economy. Government revenue comes primarily from receipts from various taxes such as income tax and value added tax (see DIRECT TAX, INDIRECT TAX), NATIONAL INSURANCE CONTRIBUTIONS, and miscellaneous sales, including the proceeds from selling off State industries. Government expenditure is directed towards a variety of current and capital commitments. A large proportion of current spending is taken up by social welfare payments (social security and unemployment benefits (JOBSEEKERS ALLOWANCE), old age pensions etc.) and the payment of wages and salaries to central and local authority employees in the Health Service, schools etc. National defence payments also take up a sizeable part of current spending. Capital spending is undertaken on various projects, including investment in infrastructure (roads, schools, hospitals and other public works) and the nationalized industries.

Taxation and government expenditure changes are used by the government to redistribute income and WEALTH (see DISTRIBUTION OF INCOME) and to influence the total amount of spending in the economy. For example, if the authorities consider it necessary to reduce total spending, they can aim for a budget surplus, increasing taxes and cutting government expenditure. Alternatively, if a stimulus to the economy is needed, the government can run a budget deficit, cutting taxes and increasing government spending.

Recently (post 1997) the government has accepted that fiscal stability is an important element in the fight against INFLATION and UNEMPLOYMENT. To this end, fiscal ‘prudence’, specifically a current budget deficit within the European Union's MAASTRICHT TREATY limits of no more that 3% of GDP (and an outstanding total debt limit of 60% of GDP) was endorsed as being a necessary adjunct to avoid excessive monetary creation of the kind which fuelled previous runaway inflation.

In fact the government has gone further than this in adopting the so-called ‘golden rule’ which requires that the government should “aim for an overall budget surplus over the economic cycle (defined as 1998/99 to 2003/04)” with some of the proceeds being used to pay off government debt to reduce outstanding debt eventually to 40% of GDP. Along the way it has introduced more rigorous standards for approving increases in public spending, in particular the ‘sustainable investment rule’ which stipulates that the government should only borrow to finance capital investment and not to pay for general spending. In addition, the government has announced it will ‘ring fence’ increases in particular tax receipts to be used only for funding specific activities. For example, receipts from future increases in fuel taxes and tobacco taxes will be spent, respectively, only on road building programmes and the National Health Service. See PUBLIC SECTOR BORROWING REQUIREMENT.

budget (firm)

a firm's planned revenues and expenditures for a given future period. Annual or monthly sales, production, cost and capital expenditure budgets provide a means for the firm to plan its future activities, and by collecting actual data about sales, product cost, etc., to compare with budget the firm can control these activities more effectively.

(b) UK budget deficits and surpluses, 1979–2004. Source: UK National Accounts, ONS (Blue Book), 2004.

budget (government)

a financial statement of the government's planned revenues and expenditures for the fiscal year. The main sources of current revenues, as shown in Fig. 18 (a), are TAXATION, principally income and expenditure taxes, and NATIONAL INSURANCE CONTRIBUTIONS. The main current outgoings of GOVERNMENT EXPENDITURE are the provision of goods and services (principally wage payments to health, education, police and other public service employees), TRANSFER PAYMENTS (old-age pensions, interest payments on the NATIONAL DEBT, etc.) and social security benefits. The budget has two main uses:- it forms the basis of the government's longer-term financial planning of its own economic and social commitments;

- it is an instrument of FISCAL POLICY in regulating the level (and composition) of AGGREGATE DEMAND in the economy. A BUDGET SURPLUS (revenues greater than expenditures) reduces the level of aggregate

demand. By contrast, a BUDGET DEFICIT (expenditure greater than revenues) increases aggregate demand. Fig. 18 (b) shows UK budget deficits (and surpluses) over the past two decades.

Recently (post 1997) the government has accepted that fiscal stability is an important element in the fight against INFLATION and UNEMPLOYMENT. To this end, fiscal ‘prudence’, specifically a current budget deficit within the European Union's MAASTRICHT TREATY limits of no more than 3% of GDP (and an outstanding total debt limit of 60% of GDP), was endorsed as being a necessary adjunct to avoid excessive monetary creation of the kind that fuelled previous runaway inflation.

In fact, the government has gone further than this in adopting the so-called ‘golden rule’, which requires that the government should ‘aim for an overall budget surplus over the economic cycle’ (defined as 1998/99 to 2003/04, with some of the proceeds being used to pay off government debt to reduce outstanding debt eventually to 40% of GDP Along the way it has introduced more rigorous standards for approving increases in public spending, in particular the ‘sustainable investment rule’, which stipulates that the government should borrow only to finance capital investment and not to pay for general spending. In addition, the government has announced it will ‘ring-fence’ increases in particular tax receipts to be used only for funding specific activities. For example, receipts from future increases in fuel taxes and tobacco taxes will be spent, respectively, only on road-building programmes and the National Health Service. See PUBLIC SECTOR BORROWING REQUIREMENT, PUBLIC SECTOR DEBT REPAYMENT, DEMAND MANAGEMENT, PUBLIC FINANCE.

budget (household)

a household's planned income and expenditure for a given time period. The household's expenditure will depend upon its DISPOSABLE INCOME, and the THEORY OF CONSUMER BEHAVIOUR seeks to show how households, or consumers, allocate their income in spending on various goods and services. See CONSUMER EQUILIBRIUM.budget

(1) An itemized list of expected income and expenses over a period of time. (2) An estimate of particular monetary needs, such as a capital budget for construction or a development budget for construction and business ramp up to break even.